Learning to Receive

Transcript of Jeffrey’s interview with Celeste Neuhaus, interdisciplinary artist, witch, and creativity guide (celestedneuhaus.com)

Sacred Practice: Painting as Homage

Celeste: I’m struck by the act of image making with paint, and how that holds meaning in and of itself now, and how that meaning has shifted over time. My undergraduate degree in painting was twenty years ago. At that time painting was received so differently. Now with all of these ways we can make imagery through AI, it’s immediate. Generative. The care and the time and the hand and the touch of making the painting convey a totally different meaning in this context.

What would you say about the choice of that process and how it relates to the homage that you’re paying each of your subjects?

Jeffrey: You just said it. Using a paintbrush, the first and foremost goal is to pay homage to the person. It’s really a sacred practice for me. I see everything as sacred in the world. So if there’s a goal, it’s for the language I’m speaking to be not so much at the person, but to allow the person to come through the painting.

Someone recently asked me what my process for painting was like. She’s a painter and a potter. I said for me it feels more like carving. I’ve always felt more like a carver, like something’s being carved out of stone. Not literally, but that the form or the image or the spirit that I’m trying to evoke, or that’s coming through me, is already there. I’m just trying to find it. So at first I’m not thinking about color, light, all those things. I’m just trying to be in dialogue with the canvas and the brush. I love the way a brush feels on canvas. The bounce, the touch. There’s something very sensitive and subtle about that. And I want to find my way in. That’s where the form starts to emerge.

So yes, you’re right. You could just blow up giant photographs and have stories with them and have this type of exhibit. But to me it’s the time, it’s the relationship with the paint. It’s the organizing, it’s the listening through the process of the painting. It’s finding the light. It’s the carving with light. It’s finding the shadow. It’s the form emerging. It’s the reworking of it.

Another thing about painting for me is that stepping back. Stepping to the canvas and then stepping back away. Like breathing to me. It’s like breathing in, then stepping back and breathing out. This becomes an intimate relationship that I don’t get from just putting up pictures. There wouldn’t be that whole investment for me.

I’m not saying that photography isn’t beautiful and that photographs didn’t play a role in this. I use sketches and photos and memory and conversation. I take walks with folks as a way to elicit that information, that data.

I believe light really is data flow. And that’s what the painting is doing. It’s reflecting and absorbing that light to retell that story and to hold it alive. Because to stand in front of a painting, it is alive. Whether you read the stories or listen to them, the painting itself holds a memory of the relationship. And I believe there’s energy in the paint. And hopefully if I’ve done my job well, when you stand in front of it, you can feel that too.

Architecture as Anchor, Abstraction as Spirit

Celeste: I want to ask you about your loose and expressionistic, almost gestural abstraction. There are areas where if you isolated them, you wouldn’t necessarily be able to identify what you’re looking at. And then there’s a real photorealism and detail happening in other places. For example, the painting with the drummer. The windows are treated very realistically. But then you have this charged air happening with this ripple effect coming out from the center of the drum, and you’ve got these bubbles happening. So there’s this interplay of the photorealism and other choices that lean toward abstraction. How have you made those choices?

Jeffrey: Looking at that painting right now, it seems architectural. I realize that all my paintings, even if they’re not an interior space like that one, are so much about the architecture of the building that we’re in.

I met Yamoussa here in this building. I could say two things about that. One is, when I look at all the paintings, there is an architecture of each of the spaces that I locate people in. The choice you’re asking about, the photorealism, it feels a little tighter in the brush stroke, right? It’s more finished. It’s more refined. That shows up when I want to make sure that I am documenting the place. It goes back to that paying homage again, or trying to honor a person in the space. I want you to know that’s right here. This happened right here. This is the space the person brought me to. This is important. So I want it to be as realistic as possible. Almost like a map you could use to find this place and stand there too.

I feel it’s important to demarcate the space that’s important to the person. That seems like a way to pay honor to them. I’m going to pay extra attention to that, which shows up as the brush strokes that are more photorealistic. I’m not as free with it because I want it to look that very specific way.

You mentioned “charged air.” I love that, because the architecture sets up the ability to play. I want to know that the painting not only looks like the person, but is embodying the spirit of the person—because that’s what I see when I’m looking and I say, “I see.” It’s not just the physical attributes of a person that I see. It’s their energy, it’s their spirit. These two things play off of each other. The photorealistic quality anchors the painting and makes the spaciousness with which I want to make invisible things—energy—visible. That’s where I can play or let the paint dance a little more, or have a spirit that maybe feels contrary to the physicality of the architecture, if that makes sense.

In the case of Yamoussa, he was playing music when I was painting him. I was thinking, “How do you represent sound? How do you paint sound?” There was energy just flying out of this guy and the instruments.

So I met with him again and said, “The first time I met you, I took some pictures and I listened for a long time, but I didn’t ask about the song you were playing. Do you remember the song?” And he told me the history of that beat and rhythm. It was a song of warning in war time, warning of the enemy’s location being sent to distant mountains and tribes. So that story, how do you represent that? I was looking for ways to feel into that more. That’s probably why that part of the painting feels more free, more abstract.

Intimacy Sparks Magic

Celeste: There’s an extension of that, where it’s not just about realism versus abstraction. There’s also a thing happening in several of the paintings where there’s realism and magical realism happening. A different correlation. It’s not just abstraction or how do you paint sound. You made the choice to show your actual bone through your pants there. You wrote lyrics in the ice. There’s a choice to distance yourself from the image. It’s already a reproduction, and now you’re seeing it through a phone.

So there are different treatments happening. Some are straightforward portraiture. The person is immersed in the environment and an extension of the environment. Then some of them have these more illustrative treatments or symbols imposed or superimposed.

Jeffrey: I think that has to do with my relationship to the person that I’m painting. In the case of my own self portrait, I know this person well, right? This is me and the story is partly about surgery and the physical inner space of my body. Trying to figure out how to represent that, I felt like I could take more liberties. I can be more magical. Whereas Ciora’s painting, where I’m looking through the device of the camera, I probably have the least relationship with her. So even though it’s still a very intimate picture and very much about her and her work, I am seeing it more removed. I’m looking through a camera, it’s showing the camera, using the device to speak about what it means to view something through a camera and what it means to record something. What is truth?

And because the video player on the camera is showing you it’s at the end of the recording, it’s using that device to hopefully ask questions of what just happened here? what happened before? What was recorded that I’m not seeing?

Celeste: And the figure in the center appears to be floating.

Jeffrey: Yeah, she’s definitely floating.

Celeste: Magical realism.

Jeffrey: Yes. And also, not everything is intent. There’s a lot of mystery to how things show up in the work and play. And then when I see it, it’s “Oh, that feels right.” In Ciora’s painting, I really wanted to focus on her. You can see in almost every painting that the person is centered as if you would draw an X through it. Carol over here, if you draw an X In that painting, her tattoo, her heart is almost dead center. That’s intentional. She’s not quite dead center, but she, and the names that she’s speaking out that are represented in the signage on the building, are centered in this painting that is in two. I use that device a lot to kind of center things.

I witnessed this march that she was leading, and at some point she asked all the white pedestrians to support and encircle the black women. So there’s a circle there. Circles often show up in my work.

Think about the architecture. Again, the space is a circle. I was on the outside looking in, and I couldn’t see her very well. How do you make a painting about someone you can’t even see? S what if I elevated her? Because that is what I’m trying to do and what I’m trying to say in this painting. Also I was drawing on history and lore and the black community’s myths and stories about liberation and being freed and rising above oppression. So that was part of that device of floating as well.

Plus I like the horizontal nature of splitting the painting in two halves. One is maybe dawn or a time that is a setting time, and one is like morning or a new time that’s coming. And she’s straddling those two. So visually it just worked for me.

Making the Invisible Visible

Celeste: Since you just said it, I wanted to ask about your choosing between horizontal and vertical. They’re very pronounced in these compositions. I’m seeing this one here that’s very much about the ground, the earth. The horizon bringing you this sense of groundedness. He is sit seated on the ground, below the ground. It formally does the thing it’s depicting. Then we have the verticality of this moon and this position and this receptivity.

Some are less of a direct correlation. We’re in this church space, the sound rises, but he’s not smack dab in the center. So you’re getting more of a sense of the space that he’s in. For some the space and the environment are what’s coming forward more.

Could talk about the way that you composed these aspects?

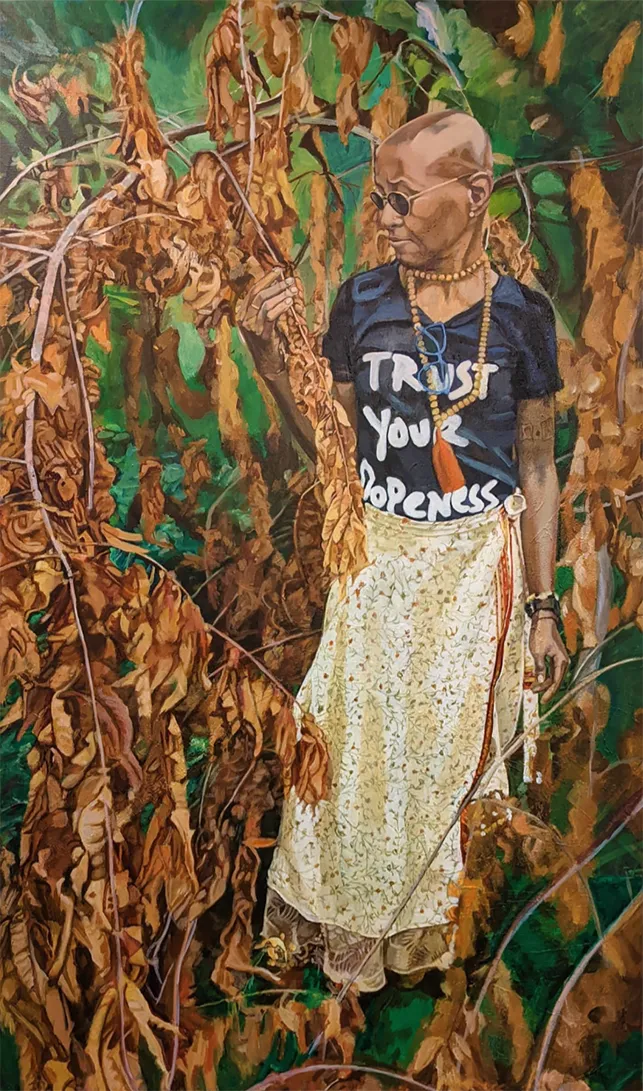

Jeffrey: You’re right that not everyone is smack dab in the middle, but I think an axis is showing up in the paintings. In the case of yvette’s in the foliage, the tree branches, she is swaying off to the viewer’s right. But the branches she’s holding balance her. They are almost holding her up by swaying off to the left. Together they create almost a heart shape, which is still centered, adding emphasis to the piece she’s holding. It puts that in the center. I would say the architecture of that painting is very much like a looking-through. The gesture is the holding of the heart.

The one with Yamoussa and the drums, you’re right, is not dead center. But he’s balanced between the bubble things that are rising, this energy that’s rising up from his hands as he’s releasing from the drums.

I’m realizing that there’s a dichotomy in many of these paintings. Two different worlds are bumping up against each other in Yamoussa’s painting. I was very cognizant of this being located in a Protestant church. It’s very western, high form of art, the architecture of these neogothic windows. And he’s playing these handmade African instruments. So there’s contrast in that. I think that’s part of why I chose to set him a little differently in the space.

You mentioned the verticality of “Her Crown is a Dome of Stars,” Denise’s painting. It was all about the moon and being out in moonlight. I didn’t set out knowing how that was going to show up. I really wanted to paint moonlight. When we got there, I was watching her perform these different rituals in nearly complete darkness. I realized when the moon came out that it was really above and in front of her. So the moon’s not in the painting at all. It’s the light that’s just gently touching on her face, making her visible. But what’s behind her is the stars, and the spinning of the earth is indicated like a time lapse photograph.

That shows up in my work a lot too, where I’m trying to indicate a collapse of time and space. We were out there for an hour and a half. Time was passing. How do you show that in a painting that is still? So this idea of movement with line, with color, with light is another way the energy may appear. Sometimes it becomes even more abstract—the air and energies that are in between—in this case I use the stars to do that. That isn’t what it looks like if you just were to look at a star, but over time that’s what it feels like.

Then similarly, in Ashley’s painting “Heartache and Home,” I’m trying to figure out how to paint mist, light, water that’s evaporating while light’s hitting it. As I played with that, all of a sudden the dots on her dress started to become watery and either slipping off jumping on the dress, I’m not sure.

Once I feel like I have the architecture of the space and the resemblance of the person, then I can play with what’s happening in the moment. I can let go of what’s really here and sense into what I really feel about the space. And how does that start to show up?

And as you said about Leonard’s, “I Am His Focus,” there’s just this heavy groundedness. He’s got a physicality about him. He’s very sincere. He wants to learn. He’s so generous. And yet when he set up to do this meditation I wanted to catch that physicality and that strength, but in a way where he felt really vulnerable. So getting down below and looking up at an angle felt like the right posture to evoke all those characteristics.

No Separation

Celeste: Some of your figures are enmeshed in the environment, like the environment is an extension of the body. Like there you have the cushion and the angle of the cushion is through her chest, through the dog, right? It’s like you’re making her body and her environment one. And that happens in this one also, in the way that the dabs of color all along the dress are the same palette as her environment. One is crystallized, focused, and one is nebulous. I don’t know what to call it other than an atmospheric version of the solidity.

In one painting your treatment of the figure is super impressionistic, compared to another which is a solid portrait. In one she is part of the environment, almost as though she’s a feature of it. As opposed to another that’s like a painting of space, of light.

So another version of the question that I asked you before. How do you make that call? Some are very complete as portraits. Some of them feel looser and more impressionistic.

Jeffrey: To be honest, as much as I want to say I made specific choices, some of it is how well I know the person. With Carol I’m thinking, “Carol is the couch.” I know Carol well. And the poem came out of that too. Some that are even more woven with the environment that they’re in have elicited me to write poems. It’s a way of trying to explain exactly what you’re noting. Her energy, her body, her gesture is saying exhaustion. And the couch is there holding her and it’s almost like she becomes couch.

With people I know less well, it feels more like a traditional portrait. There’s a little less play with the person. And maybe that’s where I choose different elements to play with.

I also think of my Buddhist training, about the five Buddha families and these different energies. When I look at this painting of Susan in the chair, I think about how it’s white, it’s space, it’s that Buddha family. That’s the element there. So she’s becoming part of the space in some ways. she’s literally even wearing white. I don’t mean it to be that literal, but looking back on it now, that whole painting is about air and light and… not a sense of weightlessness, because there’s weight to it, but if you look the way she’s seated in the chair, gravity’s not really pulling her down.

Celeste: Also sometimes the perspective is distorted. So that is another thing that plays with space.

Jeffrey: Yeah. I love using formal three point perspective, then knocking it askew or increasing the foreshortening. In Leonard’s, his hands are a little oversized to emphasize that his shoes are oversized.

My spiritual practice says that nothing is really separate. So when I’m painting, yes, we’re separate as beings, but there’s this duality that’s happening. In some cases, like Carol, she’s separate from the couch. But she’s also not. The energy, the color. And we see that in light. Even if you don’t have a spiritual practice that says this, if you look at anything as light is bouncing around, the colors are going to be reflected. There’s reflections in the person. So I’m looking at the energy, those invisible energies that are around the figure. And the more I bring those to the forefront, the less separation there tends to be from the way I’m thinking of the person and their environment.

Getting back to one of your earlier questions about abstraction and the play with the brush strokes. In Leonard’s, there’s all this foliage in the background. But when I look at it, I see energy coming out of his hands. But is that energy or is it brush strokes or is it leaves? And it’s more subtle there than it is in Yamoussa’s, where he’s got bubbles coming out of his hands. But it’s the same idea. It’s just using different devices or techniques to try to evoke that.

It’s the same with yvette. This repetition of thousands of leaves. These abstract brown forms that really represent—she says it herself to me—they represent the ancestors living and dying, surrounding us. Then she has this amazing print in her wrap that she’s wearing, that is a very delicate version of foliage and flower. And it’s looking like it’s just blooming. It’s almost the opposite. So again there’s that dichotomy of life and death, or western and eastern. I like to play with those worlds.

Honor the Details, Attend to the Sacred

Celeste: Which leads me to my next question, which is about patterning and adornment. The stained glass windows and the care you put into replicating them gives a counterpoint for another dynamism that’s happening. The care you put into the intricate pattern on her skirt—you could have faked that. You could have done some sort of loose, gestural reference to it. But instead it’s really painstaking, almost like you did the embroidery. That in relationship to the wild, loose, organic nature of the branches and the gestural text on her shirt, it’s not exactly a duality, but there’s the detail providing the ground for the expressive and the loose and the wild to read the way it does.

Jeffrey: The patterns are another way for me to dig deeper. When she wore that skirt, I knew immediately that was what I wanted to paint her in. Plus I love the contrast of the t-shirt, with this bold “Trust your Dopeness” or “Openness” or however someone might read that, next to this super delicate little print. I mentioned about feeling like I’m carving a painting. Maybe sewing would be another way to talk about it.

How much time and care does it take to make this silk fabric? That seems important to me, to be authentically honoring this person. I’m not just honoring them. Everything is sacred to me. So it’s honoring the fabric, honoring the beads that she’s wearing. Honoring the metal, honoring her tattoos. They all demand care and attention. And that gets me deeper into the spirit of person of place. Even thinking about all the people that made the fabric, it’s a meditative act for me to make a painting. It takes me beyond what I see, into the creation of the thing that I’m painting, the creation of the thing that she’s wearing. It pulls me into to a deeper state when I’m painting, which then allows me to be more of a channel to the spirit that I’m trying to be in relationship with.

Asking for Permission

Celeste: There is a numinous aspect with the inclusion of the ancestors in so many of these paintings. You are providing a kind of vessel to capture both the spirit of the subject and these other numinous forces. I noticed the underpainting that shows the carving of the names of the people killed, which serves as a sort of skin of the painting. The skin of the painting reveals a marring that overlaps with her skin. So both the environment and her skin, it bleeds through, but it actually has the surface quality of burning or branding. So those moments where there’s meaning being made that’s coming from outside of you and outside of the subject, I find that completes the work. It’s like something outside of you both is stepping in to complete the work.

Jeffrey: I love that you pick up on that. In every painting in this body of work, there was a point where I literally was stopped from painting. Not like I had to take a break, but like something else needed to come through that I wasn’t ready to receive, or I didn’t know yet, or hadn’t happened. All of them were set aside at one point. After the third or fourth time that happened, I started laughing about it. I would start the next one and I was like, okay, I wonder when that’s going to happen. And then it would show up inevitably again. It was almost like asking for permission. It’s like trying to honor someone and their ancestors so much that it’s like asking for consent. Is this next level okay to be revealed? Like earning the trust. Maybe it’s more about the willingness to try to s little delicate vine. It’s like I’m trying to prove that I’m trustworthy. Then eventually it comes. If it’s supposed to come out there’s, “Oh yeah, this isn’t the painting that wants to be seen.”

Like I needed to see it so that I could have that treatment. I could have this feeling that there’s pain, and I’m trying to find a new way to apply it. But just because I’m led to that process doesn’t automatically mean that’s the thing that wants to be seen in the end. It’s just like an ingredient. It’s embedded.

Another thing about patterns that I see when I look at Yamoussa’s shirt and the glass, the leaves in Yvette’s clothing and environment, the dots in Ashley’s dress and the creek. The curtain patterns. That’s another way of trying to show this non separateness. it’s like camouflage almost. It’s like when you start to blend in or look like the environment that you’re in and vice versa, the environment around you starts to emanate your energy, your light, and there’s not as much separateness anymore. They fit together. So there’s a holding in space as opposed to a occupying of space.

Which makes me think of things like land acknowledgements, or the homage to the ancestors. We don’t just show up here. we didn’t just land in this space. We’re trying to be in harmony with a space. We are of the space. We are asking permission to walk here, to be here, to step in a sacred space. That’s what I’m trying to evoke.

In Evaine’s painting, this one with the tube that’s protecting this sapling and she’s looking in with a mask. When I look at that, I know that she’s physically looking down into a tube. But when she did that, when we were in person together on this walk and she ran over to look, what I saw was her looking inside herself. And the painting is called “Wellspring.” To me the wellspring is what’s coming up through her, not just what’s in front of her. It’s evoking this inner energy.

People's Stories Are The Point

Celeste: When I saw that, I thought of the central channel and the illumination from within. The light is not originating from within the tube. But there is light revealing from the inside what’s in there. I thought, “Oh, that’s funny, she’s talking about the protection actually inhibiting the growth and causing what’s inside to rot, and it being time to liberate the growth from the protection.” That’s an interesting element. We can view these paintings as opportunities to embody the spirit of the person. This added layer of hearing the voice of that spirit adds another element. It makes the painting time-based, or emphasizes that it is a frozen moment in time, as we’re listening to the audio—a time-based medium allowing a voice to come forward from the imagery.

Do you want to say anything about the choice to include the audio? It does make them something other than paintings.

Jeffrey: From the very beginning, when I started the first painting, maybe long before, I’ve always had an interest in people’s stories. Growing up, I was interested in paintings and art history. As I learned, I realized I was looking at people and had no idea who they were. Occasionally you have a writeup. Often they were very prominent figures. In the case of a wealthy patron or someone with power, often they didn’t even take the time to sit. They’d have someone sit in or the body was not actually the person, and then the head would just get plopped on. That feels like exactly the opposite of what I’m trying to do. Care wasn’t taken. It could still be beautiful and there could be the gleam on the jewels and the diamonds. It can all be there, but it doesn’t feel like the spirit of the person.

Also these are just normal people. I see everyone that way. And I’ve always wondered about those paintings I studied in art history, maybe they didn’t even get paid to model, or their life wasn’t considered worthy enough to know about. They were really being almost used by the artist to paint some ideal or to represent someone else. I want these paintings to be about the person that I’m painting. And just by the fact that they are living, breathing humans, they are sacred and worthy of my time and energy and care, and your glance and your interest.

So adding the story and letting them speak does a couple things. One, it’s satisfying my interest about who is this person in this painting? I want to know, and I’m getting to hear from them directly. In fact they knew that someone would be staring at the painting when they did the interview. At the end of the recordings, a lot of them are saying, this is how I feel about you staring. Which I love, because it keeps you in very much in relationship with the painting. You can’t look away. You can, but you can’t deny it. It’s their truth and you have to witness that.

The second thing is harder to express. I don’t know if I’ve ever really seen myself as a painter. I know that I use paint in this case, and I create in other ways too, but it’s more the story that I’m getting at. So I’m going to use whatever I can. If magic will help me, I want to use magic. If ritual will help me, I want to use ritual. If the paint will help tell the story, great. If words will help, great. As long as it’s serving the purpose of eliciting the sacred nature of this person in this moment.

Even the hyper-stillness of these—someone said to me, “there’s a stillness to these, almost like you’ve caught a moment that I’m not supposed to see.” I thought that was a really interesting interpretation because it’s exactly the opposite. It’s so sacred, we miss this moment a lot. So I’m trying to slow things down so much that you can’t miss it.

So I’m hopeful that if all you wanted to do was just look at the painting, that there’s an honoring of that person and that there’s something for you to get caught in the story with visually. So it’s not like I need all those other things. It’s that I’m inviting those things because to me they add more layers of truth.

And to be transparent, as a white artist, I also recognize I’m painting white male privilege. I can say so much about my experience with some of these people, but I can’t tell their story. So by them offering their voice, they have agency. I’m not taking their image, I’m asking for consent. I’m not telling their story. I’m telling my version of how we met and how the painting came to be, and then they get to do the same. And in that way it does feel very much like a co-creation. I’ve always felt that even though I was the painter, these feel very much like co-creation.

Learning to Receive

Celeste: Coming to this painting of you, it’s actually probably the least revealing and identifiable of any of them. Your, right half is totally obscured and could be anyone. Your body sort of functions as the black background for the x-ray that emerges.

Jeffrey: I like that you mentioned that it’s almost the least revealing. Again, some of that is intention and some of that is…. Let me start with the obvious. I do think that every painting I make, and hope that any act that I undertake, is a gesture of love. Making paintings for me is an act of love. And being in relationships with these people, each one is its own love story. And not to sound cliche, but I sincerely feel the sacredness of that relationship.

So this one that’s my own self portrait is that with myself. It is this seven year journey, with one side being the start and the other side being… Not really an end. A journey of coming to deepen a relationship with myself, and really learning how to love and accept myself, and appreciate what I have to offer. And my voice. Finding my voice, which has transformed through being in relationship with all these other people along the way.

I mentioned that every painting stopped at one point to wait for more data or something to be received. There was also a point in each one where I suddenly saw myself. It was almost as if I was painting a self-portrait, not in a physical way, “Oh, that’s my nose,” but “Oh my gosh.” I remember Ashley’s distinctly. All of a sudden it felt like a purification. I don’t know how to put in words what I felt was happening internally. But I knew that as much as that painting was about and for Ashley, it was also about me.

So when I got to my own self portrait, which was the last painting that I painted, I wanted to bring elements of each painting into mine. So in some ways it’s more like a map. It’s like a chart. It’s like you could look at my painting and you could chart out all the other paintings. For some of them very literal. There’s one mask in this entire group of paintings, that Evaine is wearing, because I wanted something to connect us to the time of the pandemic. And interestingly, I’m wearing a mask in one side of that painting. There’s one hat—the straw hat of Julius. And I have that hat too, that I wear in the summertime at the beach. So that’s something literal. But I was trying to figure out how to do that in a way that connects all the pieces in the circle. So in some ways it’s the least revealing, but in some ways I am revealed through how you know me. By using that device, it’s saying I’m who I am because the way other people see me, and see me in relationship, and I see myself through them.

The last thing I would add about my own self portrait is it really is about a transformation of self. I’m revealing here that what’s important to me is the gesture of letting go on the left side, letting go of the water, and the receiving of the snow. A different form of water in the other hand. One whole side is mostly water. Then the other whole side is also water, but frozen. This change of state, which again gets at the animate energies. It’s change of time juxtaposed right up, smashed up against each other. That was the most important thing for me in this painting.

That’s what I’ve learned. Not just to let go, but I actually learned how to receive. And that’s what each of these paintings is about. That’s the exclamation point for me.